(And why Wikipedia is a better source than most people think!)

============

Read on blog or ReaderLarry Cuban on School Reform and Classroom Practice

Teaching Students to Navigate the Online Landscape (Joel Breakstone, Sarah McGrew, Mark Smith, Teresa Ortega, and Sam Wineburg)

larrycuban

February 11

This article appeared in Social Education, 82(4), 2018, pp.219-222.

Joel Breakstone is director of the Stanford History Education Group at Stanford University. Sarah McGrew co-directs the Civic Online Reasoning project for the Stanford History Education Group. Teresa Ortega serves as the project manager for the Stanford History Education Group. Mark Smith is director of assessment for theStanford History Education Group. Sam Wineburg is the Margaret Jacks Professor at Stanford

University and the founder of the Stanford History

Education Group.

Since the 2016 presidential election, worries about our ability to evaluate online content have elicited much hand wringing. As a Forbes headline cautioned, “American Believe They Can Detect Fake News. Studies Show They Can’t.”1

Our own research doubtless contributed to the collective anxiety. As part of ongoing work at the Stanford History Education Group, we created dozens of assessments to gauge middle school, high school, and college students’ ability to evaluate online content. 2

In November 2016, we released a report summarizing trends in the 7,804 student responses we collected across 12 states. 3 At all grade levels, students struggled to make even the most basic evaluations. Middle school students could not distinguish between news articles and sponsored content. High school students were unable to identify verified social

media accounts. Even college students could not determine the organization behind a supposedly non-partisan website. In short, we found young people ill equipped to make sense of the information that floods their phones, tablets, and laptops.

Although it’s easy to bemoan how much students—and the rest of us—struggle, it’s not very useful. Instead of castigating students’ shortcomings, we’d be better served by considering what student responses teach us about their reasoning: What mistakes do they tend to make? How might we build on what they do in order to help them become more thoughtful consumers of digital content?

The thousands of student responses we reviewed reveal three common mistakes and point toward strategies to help students become more skilled evaluators of online content.

Focusing on Surface Features

Over and over, students focus on a web-site’s surface features. Such features—a site’s URL, graphics, design, and “About” page—are easy to manipulate to fit the interests of a site’s creators. Not one of

these features is a sound indicator of a site’s trustworthiness; regardless, many students put great stock in them. One of our tasks asked students to imagine they were doing research on children’s health and came across the website of the American College of Pediatricians (acpeds.org). We asked them if the web-site was a trustworthy source to learn about children’s health

Despite the site’s professional title and appearance, the American College of Pediatricians(ACP) is not the nation’s major professional organization of pediatricians—far from it. In fact, the ACP is a conserva-

tive advocacy organization established in 2002 after the longstanding professional organization for pediatricians, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), came out in support of adoption for same-gender couples. The ACP is estimated to have between 200 and 500 members, compared to the 64,000 members of the AAP.4

News releases on the ACP website include headlines like, “Same-Sex Marriage—Detrimental to Children” and “Know Your ABCs: The Abortion Breast Cancer Link.” Nearly half of college students we tested failed to investigate the American College of Pediatricians and thus never discovered how it differed from the national organization of pediatricians. Instead, students trusted acpeds.org as an authoritative, disinterested source about children’s health. Most never probed beyond the site’s surface features.

As one student wrote, “It’s a trustworthy source because it does not have ads on the side of the page, it ends in .org, and it has accurate information on the page.” Another wrote, “They look credentialed, the website is well-designed and professional, they have a .org domain (which I think is pretty good).”

These students considered multiple features of the website. However, there are two big problems with these evaluations.

First, such features are laughably easy to manage and tweak. Any well-

resourced organization can hire web developers to make its website appear professional and concoct a neutral description for its “About” page.

Second, none of the features students noted attest to a site’s trustworthiness. The absence of advertising on a page does not make a site reliable and a .org domain communicates nothing definitive about credibility. Yet, many students treated these features as if they were seals of approval. Students would have learned far more about the site had they asked themselves just one question: What, exactly, is the American

College of Pediatricians?

Accepting Evidence Unquestioningly

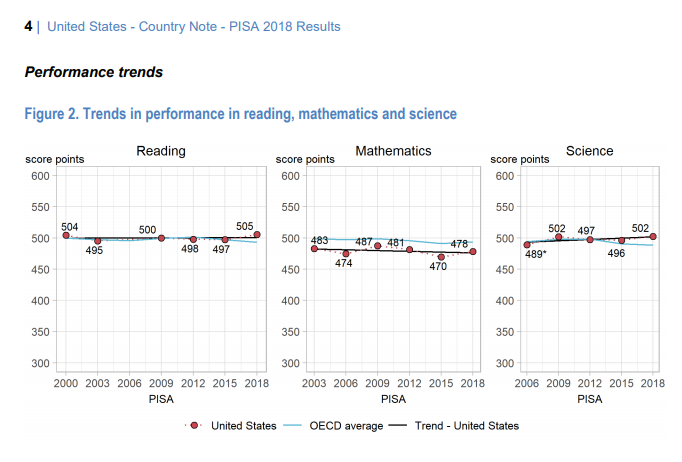

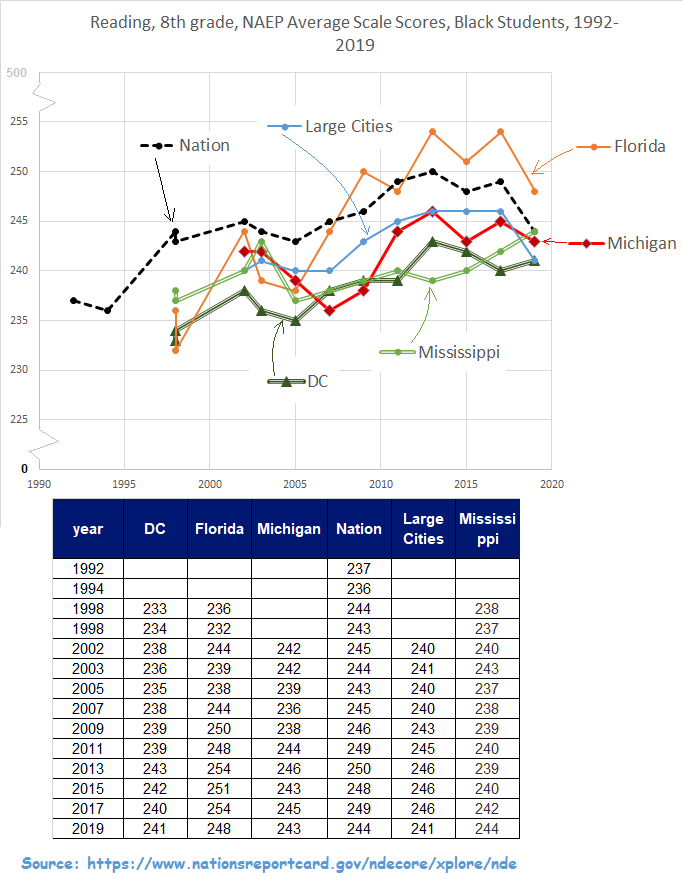

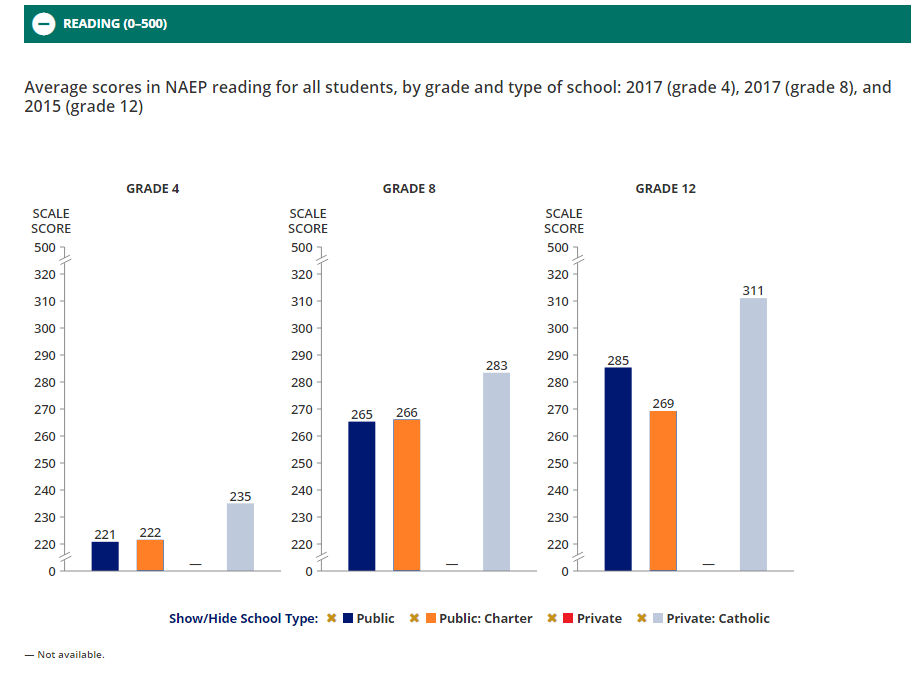

One factor dominates students’ decisions about whether information is trustworthy: the appearance of “evidence.” Graphs, charts, infographics, photographs, and videos are particularly persuasive. Students often conclude that a post is trustworthy simply because it includes evidence to back its claims.

What’s the problem with this? Students do not stop to ask whether the evidence is trustworthy or sufficient to support the claims a site makes. The mere existence of evidence, the more the better, often does the trick.

One of our tasks directed students to a video posted on Facebook. Uploaded by the account “I on Flicks,” the video, “Democrats BUSTED on CAMERA STUFFING BALLOT Boxes,” claims to capture “2016 Democrat Primary Voter Fraud CAUGHT ON TAPE.” Two and a half minutes long, the clip shows

people furtively stuffing stacks of ballots into ballot boxes in what are purportedly precincts in Illinois, Pennsylvania, and Arizona. We asked students, “Does this clip provide strong evidence of voter

fraud during the 2016 Democratic primary election?”

The video immediately raises concerns. We know nothing about who posted it. It provides no proof that it shows electoral irregularities in the states listed. In fact, a half-minute of online digging reveals that it was originally posted on the BBC website with the headline “Russian voting fraud caught on webcam.” However, the majority of high school students we surveyed accepted the video as conclusive evidence of U.S. voter fraud, never consulting the larger web to help them make a judgment.

The following answer reflects how easily students were taken in: “The video shows footage of people shoving multiple sheets of paper into a ballot box in isolated places. We can see the expressions of the people shoving paper into the ballot box and I can tell that they are being secretive and ashamed of their actions.”

Sixty percent of high school students accepted the video without raising questions about its source. For them, seeing was believing: The “evidence” was so compelling that students could see nothing else.

Misunderstanding Wikipedia

Despite students’ general credulity, they are sharply skeptical about one website: Wikipedia. Their responses show a distorted understanding about the site and a misunderstanding of its value as a research tool. We asked students to compare two websites: the Wikipedia entry on “Gun

Politics in the U.S.” and a National Rifle Association (NRA) article, “Ten Myths

about Gun Control,” posted on a personal page on Duke University’s website.

The task asked students to imagine that they were doing research on gun control and came across both sites. It then asked which of the two sites was a better place to start their research.

Most students argued that they would start with the NRA article because it carries an .edu designation from a prestigious university. Wikipedia, on the other hand, was considered categorically unreliable. As one student succinctly summed it up: “Wikipedia is never that reliable

for research!!!”

Why are students so distrustful of Wikipedia? The most common explana-

tion students provided was that anyone can edit a Wikipedia page. One student explained, “I would not start my research

with the Wikipedia page because anyone can edit Wikipedia even if they

have absolutely no credibility, so much of the information could be inaccurate.”

Another simply noted, “Anyone can edit information on Wikipedia.” While these students have learned that Wikipedia is open-sourced, they have not learned how Wikipedia regulates and monitors its content, from locking pages on many contentious issues to deploying bots to quickly correct vandalized pages.

Furthermore, these students have not learned that many Wikipedia pages

include links to a range of sources that can serve as useful jumping off points

for more in-depth research. In fact, for this task, Wikipedia is a far better place to learn about both sides in the gun control debate than an NRA broadside.

Unfortunately, inflexible opposition to Wikipedia and an unfounded faith in

.edu URLs led students astray. The strategies students used to complete our tasks—making judgments based on surface features, reacting to the exis-

tence of evidence, and flatly rejecting Wikipedia—are outdated, one-size-

fits-all approaches. They are not only ineffective; they also create a false sense of security. When students deploy these antiquated strategies, they believe they are carefully consuming digital content. In fact, they are easy marks for digital rogues of all stripes.

How Can We Help Students?

Students’ evaluation strategies stand in stark contrast to professional fact checkers’ approach to unfamiliar digital sources. As part of our assessment development process, we observed fact checkers from the nation’s most prestigious news outlets as they completed online tasks.5

When fact checkers encountered an unfamiliar website, they immediately left it and read laterally, opening up new browser tabs along the screen’s horizontal axis in order to see what other sources said about the original site’s author or sponsoring organization. Only after putting their queries

to the open web did checkers return to the original site, evaluating it in light of the new information they gleaned.

In contrast, students approached the web by reading vertically, dwelling on the site where they first landed and closely examining its features—URL, appearance, content, and “About” page—without investigating who might be behind this content.

We refer to the ability to locate, evaluate, and verify digital information about

social and political issues as civic online reasoning. We use this term to highlight the essential role that evaluating digital content plays in civic life, where informed engagement rests on students’ ability to ask and answer these questions of online information:

- Who is behind it?

- What is the evidence for its claims?

- What do other sources say?

These are the core competencies of civic online reasoning that we’ve identified through a careful analysis of fact checkers’ evaluations. When they ask who’s behind information, students should investigate its authors, inquire into the motives (commercial, ideological, or otherwise) those people have to present the information, and decide whether they should be trusted.

In order to investigate evidence, students should consider what evidence

is furnished, what source provided it, and whether it sufficiently supports the

claims made. Students should also seek to verify arguments by consulting multiple sources.

There is no silver bullet for combatting the forces that seek to mislead

online. Strategies of deception shift constantly and we are forced to make

quick judgments about the information that bombards us. What should we do to help students navigate this complex

environment?

We believe students need a digital tool belt stocked with strategies

that can be used flexibly and efficiently. The core competencies of civic online reasoning are a starting place. For example, consider what would happen if students prioritized asking “Who is behind this information?” when they first visited acpeds.org. If they read laterally, they would be more likely to discover the American College of Pediatricians’ perspective. They might come across an article from Snopes, the fact-checking website, noting that the American College of Pediatricians “explicitly states a mission that is overtly political rather than medical in nature”6

Or a Southern Poverty Law Center post that describes the ACP as a “fringe anti-LGBT hate group that masquerades as the premier U.S. association of pediatricians to push anti-LGBT junk science.” 7

Similarly, students would come to very different conclusions about the video claiming to show voter fraud if they spent a minute reading laterally to address the question, “What’s the evidence for the claim?”

Wikipedia is another essential tool. We would never tell a carpenter not to

use a hammer. The same should hold true for the world’s fifth-most-trafficked website. The professional fact checkers that we observed frequently turned to Wikipedia as a starting place for their searches. Wikipedia never served as the final terminus, but it frequently provided

fact checkers with an overview and links to other sources. We need to teach students how to use Wikipedia in a similar way.

As teachers, we also need to familiarize ourselves with how the site functions. Too often we have received responses from students indicating that they don’t trust Wikipedia because their teachers told them never to use it. Although far from perfect, Wikipedia has progressed far beyond its original incarnation in the early days of the web. Given the challenges students face online, we shouldn’t deprive them of this powerful tool.

In short, we must equip students with tools to traverse the online landscape. We believe integrating the core competen-cies of civic online reasoning across the curriculum is one promising direction. It will require the development of high quality resources, professional development for teachers, and time for professional collaboration.

We have begun this work by making our tasks freely available on our website (sheg.stanford.edu). We are also collaborating with the Poynter Institute and Google. As part of this initiative, known as Media Wise, we are creating new lesson plans and professional development materials for teach-

ers. These resources will be available on our website in the coming months.

This is a start, but more is needed. We hope others will join in this crucial work. At stake is the preparation of future voters to make sound, informed decisions in their communities and at the ballot box.

Notes

- Brett Edkins, “Americans Believe They Can Detect

Fake News. Studies Show They Can’t,” Forbes (Dec.

20, 2016), http://www.forbes.com/sites/brettedkins/2016/

12/20/americans-believe-they-can-detect-fake-news-

studies-show-they-cant/#f6778b4022bb. - Joel Breakstone, Sarah McGrew, Mark Smith, Teresa

Ortega, and Sam Wineburg, “Why We Need a New

Approach to Teaching Digital Literacy,” Phi Delta

Kappan 99, no.6 (2018): 27–32; Sarah McGrew,

Joel Breakstone, Teresa Ortega, Mark Smith, and

Sam Wineburg, “Can Students Evaluate Online

Sources? Learning from Assessments of Civic

Online Reasoning,” Theory and Research in Social

Education 46, no. 2 (2018): 165–193, https://doi.

org/10.1080/00933104.2017.1416320; Sarah McGrew,

Teresa Ortega, Joel Breakstone, and Sam Wineburg,

“The Challenge That’s Bigger Than Fake News:

Civic Reasoning in a Social Media Environment,”

American Educator 41, no. 3 (2017): 4–10. - Stanford History Education Group, Evaluating

Information: The Cornerstone of Civic Online

Reasoning (Technical Report. Stanford, Calif.:

Stanford University, 2016), https://purl.stanford.edu/

fv751yt5934. - Warren Throckmorton, “The American College of

Pediatricians Versus the American College of

Pediatrics: Who Leads and Who Follows?” [Blog

post], (Oct. 6, 2011), http://www.wthrockmorton.

com/2011/10/06/the-american-college-of-pediatricia

ns-versus-the-american-academy-of-pediatrics-who-

leads-and-who-follows/. - Sam Wineburg and Sarah McGrew, “Lateral

Reading and the Nature of Expertise: Reading Less

and Learning More When Evaluating Digital

Information,” Teachers College Record (in press),

Stanford History Education Group Working Paper

No. 2017-A1, Oct 9, 2017, https://papers.ssrn.com/

sol3/papers.cfm? abstract_id=3048994 - Kim LaCapria, “American Pediatricians Issue

Statement That Transgenderism is ‘Child Abuse’?”

Snopes (February 26, 2017), http://www.snopes.com/fact-

check/americas-pediatricians-gender-kids/. - Southern Poverty Law Center (n.d.). American

College of Pediatricians, http://www.splcenter.org/fighting-

hate/extremist-files/group/american-college-

pediatricians.

CommentLikeYou can also reply to this email to leave a comment.

Larry Cuban on School Reform and Classroom Practice © 2024. Manage your email settings or unsubscribe.

Get the Jetpack app

Subscribe, bookmark, and get real-time notifications – all from one app!